Fall '25 - Everyone's A Critic

Yes, Virginia, there was a time when rock critics were our only defense against sell-out Rockstars and the hostile corporate takeover of popular music. They were expendable.

In the September 8th edition of The New Yorker, Kelefa Sanneh posted the essay “Everything Nice: How Music Criticism Lost Its Edge.” His column made me think back with a smile to my younger days reading rock critics like Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, John Rockwell, Lester Bangs, R. Meltzer, Ellen Willis, Steve Morse, Kurt Loder, and others in publications like Rolling Stone, The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Village Voice, Creem, The Soho Weekly News, and New Musical Express. These guys made their living writing about music and defending the faith, armed only with a FM/cassette Boom Box, a Smith-Corona Galaxis Deluxe, cheap whiskey, and some amphetamines. They saw themselves as music industry outsiders with an obligation to keep the corrupt record executives somewhat honest. They were all too eager to call bullshit on record companies and artists they thought were pandering to listeners for a quick buck. The dyspeptic reviews they published were often cranky and vicious, but very funny. Sanneh is much younger than me and recounts his first exposure to rock criticism.

" The first music review I remember reading was in Rolling Stone, which rated albums on a scale of one to five stars, or so I thought. In 1990 the debut solo album by Andrew Ridgeley, who had sung alongside George Michael in the pop duo Wham!, was awarded only half a star. The severity and precision of the rating seemed hilarious to me, though probably not to Ridgeley, who never released another record."

Mission accomplished! The music consumer would be forever protected from Ridgeley’s work. Later in the piece Sanneh cites the music review site Pitchfork, founded by Ryan Schreiber in 1996. It started with a “Rockist” sensibility with a focus on loud indie guitar bands. Schreiber recounts the pressures from inside and outside Pitchfork to widen its scope to be inclusive of other genres like country, rap, and, yes, pop music. It became known as “poptimism” as over the years Pitchfork took a more inclusive approach, especially with hip-hop.

Taylor Swift was the final straw. Schreiber told Sanneh: “I never, ever wanted to cover Taylor Swift. It was just not part of our scope.” Some critics who included a few negative comments, even in a generally positive review of a Swift album, reported they and their families had been threatened, harassed, and doxed. It was all magnified by the moronic inferno (thanks for that, Martin Amis) of social media. Schreiber noted there were fewer negative reviews submitted for artists with huge fan bases. The purchase of Pitchfork in 2018 by publishing giant Condé Nast (which also owns The New Yorker) only increased the pressure to monetize the huge fan bases of pop stars. Schreiber left Pitchfork in 2019. It’s nice to be nice — less hassles, more profit.

The “most infamous” review of Swift’s album The Tortured Poets Department appeared on the music site Paste.

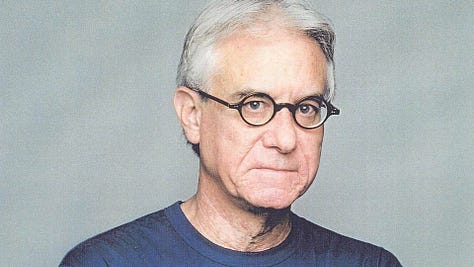

"It had a cantankerous opening sentence that Lester Bangs might have enjoyed ("Sylvia Plath did not stick her head in the oven for this!"), but no byline; the magazine said it wanted to shield the writer from potential threats of violence." On New Years Day I posted the essay 1001 Albums, which offered an age-cohort theory of relativity for music criticism. Read it via this link. It’s always amusing to review Best Of lists from critics I know to be between 45 and 75 (or even older in the case of Christgau and Greil Marcus!) and see how desperate they are to remain relevant (and publishable) for the younger generations. Year after year they include young pop vocalists just out of their teens with hit synth-pop albums favored by young women who like to dress up and go clubbing with their girlfriends.

The It Girl of Summer ‘24 was Sabrina Carpenter, whose album Short n’ Sweet and singles Espresso and Please Please Please made it onto many critics’ best of 2024 lists. I tried my best to listen to her album, but 10 minutes in I had to hit stop on Spotify. Then I found her NPR Tiny Desk video performance and watched to the 12-minute mark before bailing out. She’s attractive, has a charming personality, and a sense of humor, but no critic is going to tell me this candy confection is one of the best albums of the ten-thousand-plus released in 2024. Carpenter’s music is what we called “bubblegum pop” back in the ‘70s. I’ll remain silent on Taylor Swift to avoid death threats, or 50 pizzas delivered to my door.

There are career and commercial reasons why rock/pop critics try to rationalize this product and elevate these artists. No one wants to miss the next Taylor Swift, who became a billion-dollar industry unto herself. I don’t consider myself a critic, but rather a music writer. I have no paid subscribers (and few free subscribers ) and no commercial pressures to please a large audience. This is not my living and I have limited time to write, so I don’t spend it criticizing more talented people than me and their creative efforts.

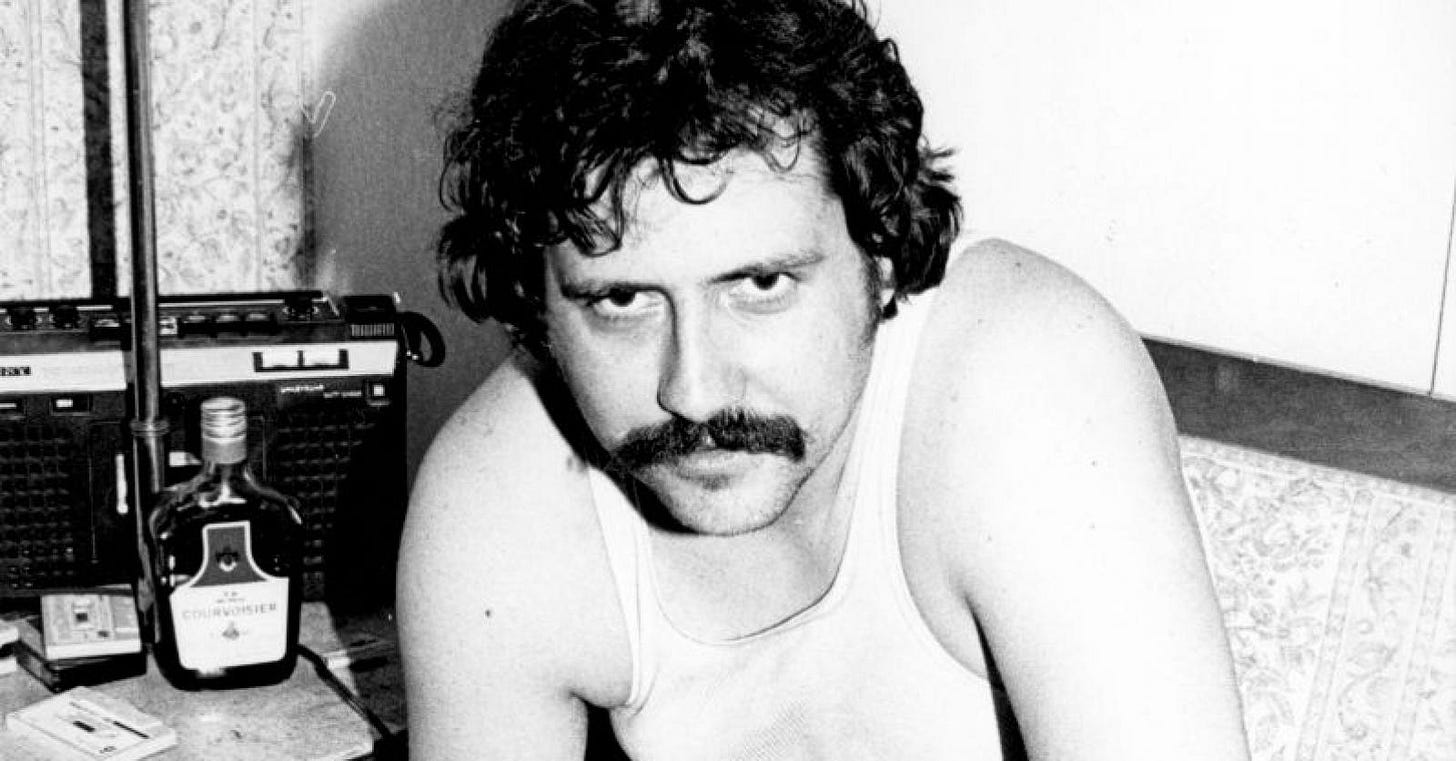

Lester Left Town

As an example of how nasty rock critics of the 1970s could be, I recommend reading the work of Lester Bangs, who covered rock music for Creem magazine and The Village Voice and decried the takeover of the AM/FM airwaves by large media conglomerates and the conformity they imposed. For Bangs the big corporations murdered authenticity in American music and corrupted formerly authentic artists. His job was to call out the perpetrators.

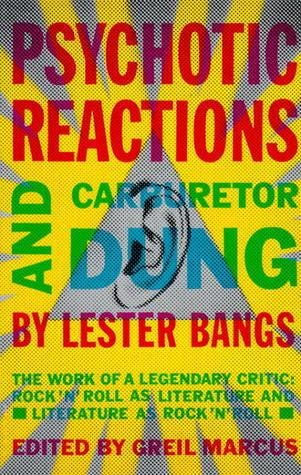

A collection of essays written by Bangs, entitled Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung (Anchor Press, 1987) was edited by Greil Marcus (who at age 80 is still writing rock criticism on Substack) and released five years after Bangs’ death at age 33 from self-medicating to the extreme. In his introduction, Marcus pays Bangs the highest tribute.

“Perhaps what this book demands from a reader is a willingness to accept that the best writer in America could write almost nothing but record reviews.”

I consider myself fortunate to have read Bangs’ missives in real time. I read almost nothing but record reviews during that period (except for assigned school reading of course!).

I learned from his reviews the true genius of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks and David Bowie’s Station to Station. I was mystified by his adoration of The Guess Who. I laughed reading essays like “James Taylor Marked for Death” or “Screwing the System with Dick Clark.” Then there were his epic battles with Lou Reed, best summarized in “Let Us Now Praise Famous Death Dwarves, or, How I Slugged It Out with Lou Reed and Stayed Awake.”

About 25 years ago Lester Bangs was almost made famous in director Cameron Crowe’s hit movie Almost Famous, a sweet 1970s coming-of-age story based on Crowe’s improbable teenage stint as a correspondent for Rolling Stone. In the clip below, Bangs, played by the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, meets young Mr. Crowe, explains how the rock music world really works, and gives Crowe his first paid assignment — $35 for 1,000 words on Black Sabbath. Watching this again, I’m smiling and glad that I read Bangs and saw this movie.

In reality, it was Bangs who wrote a scathing 1970 review in Rolling Stone of Black Sabbath‘s first album, dismissing them as imitators of Eric Clapton’s supergroup Cream.

“Cream clichés that sound like the musicians learned them out of a book, grinding on and on with dogged persistence. Vocals are sparse, most of the album being filled with plodding bass lines over which the lead guitar dribbles wooden Claptonisms from the master’s tiredest Cream days. They even have discordant jams with bass and guitar reeling like velocitized speedfreaks all over each other’s musical perimeters yet never quite finding synch—just like Cream! But worse.”

Rolling Stone’s publisher Jann Wenner fired Bangs in 1973 for “disrespecting musicians” after an especially harsh review of Canned Heat. By that year a massive corporate sell-out was well underway.

KPop’s World Takeover Bid

In addition to Sabrina Carpenter, can someone please explain to me the genius and popularity of KPop? As of last week, KPop Demon Hunters is now the most-watched original Netflix movie of all time, with over 325 million total views in the first three months of its release on Netflix. The population of South Korea itself is only 50 million.

The animated musical follows a KPop girl group named HUNTR/X that moonlights as a trio of demon hunters, fighting against evil through the power of music. Three songs from the film’s soundtrack, which has racked up over 3 billion total streams (??!!), are on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart and likely contenders for this year’s Grammy Awards. The film was so popular that Netflix brought it to theaters in August and October, in a sing-along version to delight its fans. The musical grossed over $18 million at the box office in the first two days of its August theater run.

Back on August 30th, the esteemed jazz historian, pianist, and cultural commentator Ted Gioia published What’s Going On With KPop Demon Hunters? on his Substack, The Honest Broker.

"KPop Demon Hunters just became the most popular Netflix movie of all time. In the first ten weeks after launch, people watched it 236 million times. Of course, you might not notice here on Substack. This platform is filled with culture pundits, but they’ve blissfully ignored the biggest streaming hit of the century. Writer Klaus Zynski posted the following on Substack:

'KPop Demon Hunters on Netflix is, I am not exaggerating, probably the world’s most popular piece of media at the moment and it has generated zero discourse on here beyond a few (pretty good) pieces in Korean-specific culture blogs. Very telling. There are games beyond the game.'

That’s one of the trademarks of the Korean creative miracle. It succeeds despite the critics. Or let me put it more accurately: It bypasses them. We might all learn something from that." Gioia also cites the most popular music video of all time, the Baby Shark song, promoted by Pinkfong, a Seoul-based entertainment company.

"This maddening earworm has generated more than 16 billion views. No other video even comes close. (Number two on the list, “Despacito,” only has 8.8 billion clicks.) I follow music criticism closely, but I’ve never read a single review of “Baby Shark.” That doesn’t matter. It flourishes in a world beyond criticism."

Tbis week I tried to watch KPop Demon Hunters on Netflix. I had to stop after 10 minutes. I bailed out sooner than when I tried listening to Sabrina Carpenter. Are there 325 million sixth-graders in the world and have they all seen it? As for the Baby Shark video, I’ll just take a pass.

Cutting the Cord to Pop Culture

For about 20 years, until sometime in my 40s, I attempted to stay current with popular culture in America. I watched network TV series and listened to commercial AM/FM radio for the latest Top 40 or Hot 100 hits, thinking it was important to understand the cultural messages and memes gleaned from the mass media. To me they were indicators of the direction mass culture was going and also gave me a sense of where our democracy was going. The first warning sign was the surprising rise of country music in our urbanized, tech-driven society.

I saw myself pursuing sort of a self-directed graduate program in “American Studies,” like the program offered at Yale. I tried to get into nascent rap and hip-hop, but got stuck at the Sugar Hill Gang, Grandmaster Flash, RUN-D.M.C., Public Enemy and De La Soul. I fed off their energy and anger, but as I aged it all just seemed belligerent, like the ‘70s punk I had loved, or Trump throughout his entire life.

Likewise with network TV series, I doggedly watched various police, fire, SWAT, hospital, and lawyer shows, along with three off-shoots of NCIS. They all fell flat with actors, who looked like former models with perfect teeth and bodies, delivering witless dialogue from hack TV writers. There’s always a maudlin moral delivered earnestly at the end of each episode — after the shooting, explosions and sexual violence are over.

Forget reality shows — I watched the first few episodes of Survivor and never watched another. Once HBO was part of our cable package and The Sopranos and The Wire were available, there was no going back to network programming (except for sports of course). As I entered my 50s it became easier to finally cut the cord to popular culture. No, I have not seen St. Denis or The Pitt, but I did see young Denzel Washington, David Morse, David Birney, Mark Harmon, and Howie Mandel in every episode of St. Elsewhere from 1982 to 1988. Not to mention young Noah Wyle, George Clooney, Angela Bassett, Julianna Margulies, and Maura Tierney on all 331 episodes of ER from 1994 to 2009. Don’t even get me started on Hill Street Blues and Dennis Franz as Sipowicz from 1981 to 1987.

At this point I feel like a unionized 30 and out public employee, one who has maxed out their retirement benefits. Why stay around just to get laid off in a funding cut? Join the throng heading to Florida, Texas or the Carolinas. In my case, I’ll just blissfully ignore mass culture and take my retirement in the spiritual tax havens I choose to inhabit.

I never finished my PhD in American Studies, but I’ll keep writing under the cultural radar about non-viral topics for maybe 100 people. The true zeitgeist of Pop Culture is too terrible to behold. I knew when I started writing on Substack in Fall ‘23 that I was probably creating a product for which there is zero market demand.

In our fragmented social media world, everyone’s a critic with the power to focus only on what is valuable to them. I’m not going to waste my limited time on this planet by criticizing that which someone enjoys for whatever reason. Sabrina and Taylor and KPop don’t need more coverage or analysis. They’re already too famous.

Coming Next Time

Not sure yet, but I’ll figure it out. I’ve got a bunch of drafts to choose from. The Fall ‘25 playlist on Spotify is groaning with the weight of nearly 1,000 tracks and 100 hours of music. We’ll be there by next week.

Let’s go out with the album that Hoffman as Lester Bangs in Almost Famous tosses at the San Diego DJ as the absolute summit of Real Rock & Roll. The track is Search and Destroy by Iggy and The Stooges from Raw Power (1973). It suggests a mission for the Future Rock Critics of America.